(Originally published in August, 2012, as "Our Dark Beacon: Prayer Vigil for Hiroshima and Nagasaki" on the Protest Chaplains of Chicago blog.)

Water Tower Monument

Chicago, Illinois

August 5, 2012, 6:15 PM

(Corresponds to 8:15 AM in Japan, August 6th, the exact time of the first bomb and the time of most commemoration services.)

To remember the past

is to commit oneself to the future.

To remember Hiroshima

is to abhor nuclear war.

-- Pope Paul II

ORDER OF SERVICE

Ringing of singing bowl twice (one for the bereaved families and one for the children)

Welcome and Opening Words by Joe Scarry from No Drones Network and Rev. Loren McGrail from Protest Chaplains of Chicago

O God, tender and just

the names of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

cut through our denial

that we are capable of destroying the earth

and all that dwell therein.

Forgive us---

and help us always to remember.

We must remember because this must never happen again.

We must remember because you would have us live

in harmony with each other,

seeing the joy of your creation in our

sisters and brothers.

Holy God, God of all ages,

lead us from death to life,

to the stockpiling of hope and possibilities, and of love

rather than the stockpiling of weapons, or of stones to throw,

or of hate.

Opening Ritual

(Lighting first candle and placing it in the fountain) Sixty-seven years

ago tonight, morning in Japan, a single B-29 dropped the first atomic

bomb on the city of Hiroshima. This incredible blast destroyed most of

the city and killed over 60,000 people almost immediately. Another

80,000 more died in subsequent months and years from the deadly

radiation.

(Lighting second candle and placing it in the fountain) Three days

later, another B-29 dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, killing

about 20,000 people almost immediately and about 60,000 more in

subsequent months and years from radiation.

From Mayor Matsui Kazumi’s Peace Declaration (2011)

“The time has come for the rest of us to learn from all the hibakusha and what they experienced and their desire for peace…

This description is from a woman who was sixteen at the time:

“My

forty-kilogram body was blown seven meters by the blast, and I was

knocked out. When I came to, it was pitch black and utterly silent. In

that soundless world, I thought I was the only one left. I was naked

except for some rags around my hips. The skin on my left arm had peeled

off in five-centimeter strips that were all curled up. My right arm was

sort of whitish.

Putting my hands to my face, I found my right cheek quite rough while my

left cheek was all slimy…Suddenly I heard lots of voices crying and

screaming, ‘Help!’ ‘Mommy, help!’ Turning to a voice nearby I said,

‘I’ll help you.’ I tried to move in that direction but my body was so

heavy. I did manage to move enough to save one young child, but with no

skin on my hands, I was unable to help any more…’I’m really sorry…”

Now, we must communicate what we have learned to future generations and

the rest of the world. Through this Peace Declaration, I would like to

communicate the hibakusha experience and desire for peace to each and

every person on this planet. Hiroshima will pour everything we have into

working, along with Nagasaki, to expand Mayors for Peace such that all

cities, those places around the world where people gather, will strive

together to eliminate nuclear weapons by 2020…

The accident at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear

Power Station and the ongoing threat of radiation have generated

tremendous anxiety among those in the affected areas and many others.

The trust the Japanese people once had in nuclear power has been

shattered. From the common admonition that “nuclear energy and humankind

cannot coexist,” some seek to abandon nuclear power altogether.

Others advocate extremely strict control of nuclear power and increase utilization of renewable energy…

Message From Hiroshima

Dear all,

We appreciate very much the fact that you are holding a special

gathering commemorating the dropping of the A-bomb on Hiroshima on

August 6.

The nightmarish days following the Tsunami had nearly every person in

Japan filled with fear of truly catastrophic scenarios, and actually the

situation surrounding the Fukushima Nuclear Plants still remains very

precarious and requires utmost caution.

Although one of the nuclear plants has been restarted, the mass

demonstration of anger at the government’s decision is becoming more and

more visible and intense. We hope these rising waves against nuclear

power will be united around the globe so that we can advance steady

steps toward creating a nuclear-free way of life.

On August 6 in Hiroshima, we are going to hold, beside many other events

and conferences, the 9th NO DU gathering; this year we aim to draw

people's attention to the fact that next March will mark the 10th

anniversary of the start of Iraq War by announcing that we will hold a

commemorative conference in Tokyo around mid-March next year in order to

call into question again the military use of nuclear waste, that is, DU

weapons, as a wedge problem relating to the whole nuclear cycle.

We hope you will join us in such reflection, too, and we wish you great success in your activities on August 6 and further on.

With friendship and solidarity,

Kazashi Nobuo

Director,

International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons (ICBUW) Hiroshima Office

Song: This is My Song

Excerpts from Blessing the Bombs, a speech by Father George Zabelka

“The ethics of mass butchery cannot be found in the teachings of Jesus…

What the world needs is a grouping of Christians that will stand up and

pay up with Jesus Christ. What the world needs is Christians who, will

proclaim: the follower of Christ cannot participate in mass slaughter.

He or she must love as Christ loved, live as Christ lived and, if

necessary, die as Christ died, loving ones enemies…

To fail to speak to the utter moral corruption of the mass destruction

of civilians was to fail as a Christian and a priest. Hiroshima and

Nagasaki happened in and to a world and a Christian Church that has

asked for it---that has prepared the moral consciousness of humanity to

do and justify the unthinkable…

As an Air Force chaplain, I painted a machine gun in the loving hands of

the nonviolent Jesus and then handed this perverse picture to the world

as truth. I sang, “Praise the Lord” and passed the ammunition…As

Catholic Chaplain for the 509th composite Group, I was the final channel

that communicated this fraudulent image of Christ to the crews of the

Enola Gay and the Boxcar...”

Excerpts from The Drone Summit, the Lunchbox and the Invisibility of Charred Children by Hugh Gusterson

I kept thinking about the lunchbox.

The lunchbox belonged to a schoolgirl in Hiroshima. Her body was never

found, but the rice and peas in her lunchbox were carbonized by the

atomic bomb. The lunchbox, turned into an exhibition piece, became, in

the words of historian Peter Stearns, "an intensely human atomic bomb

icon."

The Smithsonian museum's plans to exhibit the lunchbox as part of its

1995 exhibit for the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II enraged

military veterans and conservative pundits, who eventually forced the

exhibit's cancellation.

Everyone knows, in the abstract at least, that the atom bomb killed

thousands of children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But any visual

representation of this fact - even if done obliquely, through a

lunchbox, rather than through actual pictures of charred children - was

deemed out-of-bounds by defenders of the bombing.

Today, we must still make an enormous effort to bring forward visual

representations of the victims of U.S. attacks, such as in the remote

borderlands of Pakistan. Brave activists like the Pakistani lawyer

Shahzad Akbar of the Foundation for Fundamental Rights -- a Pakistani

lawyer who represents civilian victims of US drone strikes in Waziristan

(a tribal area on Pakistan's border with Afghanistan) -- are making

sure this happens.

In Japan after World War II, the US occupying authorities made it

illegal for Japanese citizens to own any pictures of the aftermath of

Hiroshima or Nagasaki. In Japan, Akbar would have been locked up by

General MacArthur.

Excerpt from The Drone and the Bomb by Ed Kinane

“The lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki belong always before us. The agony of those two cities must remain our dark beacon.

Hiroshima/Nagasaki wasn’t so much about targets as about audiences.

We---or rather, the very highest reaches of the U.S.

government---annihilated a couple hundred thousand nameless, unarmed,

undefended human beings to warn the world: “Don’t mess with us; we run

things now…”

Afghanistan/Pakistan/Yemen echo Hiroshima/Nagasaki. With its new cutting

edge technology, the Pentagon still trots out the old myth: the Reaper

drone is all about “saving our boys’ lives.”

And Bomb-like, the Reaper proclaims: “If you defy us, wherever you are, we will hunt you down and kill you.” Déjà vu.

Like Japan’s hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, the Reaper’s

civilian casualties in Afghanistan/Pakistan/Yemen fail to matter. Few

ask: What’s the human cost? What’s the blowback?”

Excerpt from Twilight of the Bomb a speech prepared by Jay Kvale

“This week an international conference on nuclear disarmament is being

held in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to promote reductions in arsenals, given

impetus by the stories of some of the last survivors of the bombings.

In addition to actual warheads, the problem of securing loose nuclear

materials is also being addressed since 1,600 tons of enriched uranium

and 500 tons of plutonium, enough to make tens of thousands of bombs,

are still scattered around, mostly in the former Soviet Union…

Teams of specialists expect to have more than 80% of loose nuclear

material from the world’s 129 research reactors secured by 2014…The

Non-Proliferation Treaty has limited the number of nations with nuclear

weapons to nine.”

Song: Lead Us From Death to Life (World Peace Prayer)

Litany of Remembrance

We remember each child born since the dawn of the Nuclear Age, the miracle and sacredness of each living being.

We remember the image of the first mushroom cloud of the Trinity atomic test rising above the earth in New Mexico.

We remember the words of Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project, “I have become death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

We will remember “ Little Boy” and “Fat Man”---the bombs that

destroyed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th

and August 9th, 1945.

We remember the 300,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki who died as a result of the atomic bombs. May they rest in peace.

Sixty-seven years, the people of the earth remember the terrible

destructive power and violence latent within us and made manifest in the

bomb.

We will meet this power of destruction by drawing on the rich sources of

our human and spiritual traditions and the deep wells of faith, beauty,

humor, and creativity of the human spirit in order to nourish a culture

of nonviolence and peace.

We will remember the cost to all life of our commitment to death.

We will remember the indigenous people, on whose land we mined for

uranium, tested our nuclear weapons, and now fill our nuclear waste.

We will remember the plants and animals of the earth, whose waters, soil, and air we contaminate in the name of “security.”

We will remember our children and grandchildren and all beings of the

future whose toxic radioactive inheritance we cannot keep from them.

We will remember our nuclear history so that we will not repeat it.

Closing Ritual

Children at the Yamazato elementary school in Nagasaki gather to

commemorate the 1,300 students who were killed when the atomic bomb fell

on their city. As part of their ceremony, they pour water on a stone

monument symbolically quenching the thirst of the bomb’s victims and

offering a prayer for their souls.

Tonight, we gather at this fountain in front of Chicago’s Water Tower,

to remember not only those students but also all the people killed by

these atomic bombs, all the civilians killed by our new drone weapons;

we remember and pray for all their souls. You are invited to put your

hands in the water---let it pour through your fingers in memory of all

those whose thirst could not be quenched. In the fountain, you will also

find some stones. You are invited to take one as a remembrance of these

lives, of this day and your commitment to work for a nuclear free world

and peace.

Liturgy for First Annual Prayer Vigil for Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Our Dark Beacon was created by Rev. Loren McGrail and Joe Scarry.

For more information on this service or other anti-war or militarism information or events contact:

Rev. Loren McGrail at lorenmcgrail [at] gmail.com or visit Protest Chaplains of Chicago on Facebook or go to Awake to Drones for writings on drone warfare and surveillance by area faith leaders.

Joe Scarry at jtscarry [at] yahoo.com for information on the No Drones Network.

WORSHIP RESOURCES

Cover Image by

Laurence Hyde: woodcut print from the novel Southern Cross, a book about atomic testing in the Pacific

from Christian Prayer by

Rev. Loey Powell, Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ.

Excerpts from

Mayor Matsui Kazumi’s Peace Declaration (2011).

Message from Hiroshima:

Kazashi Nobuo, Director,

International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons (ICBUW) Hiroshima Office.

Excerpts from

The Drone Summit, the Lunchbox and the Invisibility of Charred Children by Hugh Gusterson at Truthout | Op-Ed.

Excerpts from

Blessing the Bombs, a speech by Father George Zabelka, Catholic Chaplain for the 509th Composite Group, the atomic crew. Speech was given at Pax Christi conference in August 1985.

Excerpts from

The Drone and the Bomb by Ed Kinane, an anti-militarism activist on Fellowship of Reconciliation’s website July 28, 2012.

Excerpts from

Twilight of the Bomb

a speech prepared by Jay Kvale for Hiroshima Commemoration ceremony at

Lake Harriet Peace Garden in Minneapolis, August 6, 2012. Published on

War is Crime.org.

Litany of Remembrance adapted from Pax Christi, St. Joseph’s Watford way, Hendon, London

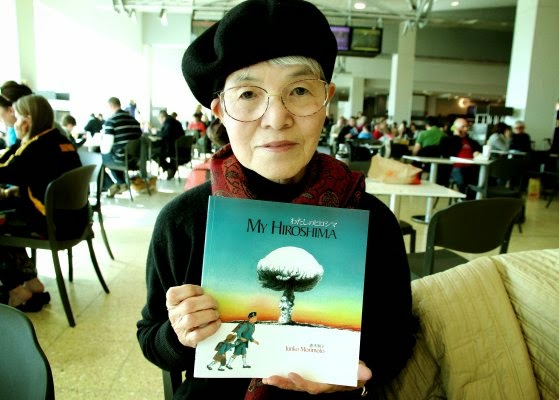

Photograph of the Closing Ritual at the Chicago Water Tower, August 5, 2012, by Meghan Trimm,

Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), Chicago

At Hiroshima, Barack Obama missed the connection between the number of

WW II deaths, 60 million, and the killing power of a single nuclear exchange today.

At Hiroshima, Barack Obama missed the connection between the number of

WW II deaths, 60 million, and the killing power of a single nuclear exchange today.